This is a copy of a comment I made during a forum discussion on “improving” the response of an amplifier.

So lets talk feedback for a minute. There are lots of ways to apply feedback and all feedback performs the same function. Any differences in feedback response are usually due to the different impedance functions applied to the feedback loop. Contrary to popular opinion, there is no magic in any feedback function. The effects of feedback are to reduce gain, increase bandwidth, reduce circuit induced distortion and noise, and decrease gain function sensitivity to circuit parameter variation. And it works. We’ve been using feedback amplifiers widely since Harold Black introduced the concept back in 1934.

Now let’s discuss the real issue. Feedback fundamentally changes the character of the amplifier. By it’s very nature (and this is demonstrated by both testing and the mathematics), the ability of feedback to reduce harmonic distortion is directly proportional to the order of the distortion. This means that the largest effects are on the fundamental waveform. This is what accounts for the reduction in overall gain. The next highest effect is on the second order harmonics, then third, and so on. So what this means is 1) the resultant THD will be lower (usually significantly lower) with feedback than without and 2) the fundamental harmonic structure with feedback will be shifted such that higher order distortion has far less reduction than lower order distortion. And this is where the disagreements over feedback begin to arise. Because of the way the cochlea works and the way brain interprets sound, small magnitude higher order harmonics have a significant impact on the way the overall tone sounds to the ear. As such, due to the differences in harmonic structure, feedback fundamentally changes the sound of an amplifier. This is all fact; plain, provable, tested, and widely accepted.

But here’s the problem. Everyone’s brain works differently. And everyone hears sound differently. What’s more, the brain is highly plastic in operation. As you listen to an amplifier, it literally reprograms your brain as you listen. This is one of the main reasons you can go back to an amplifier you haven’t used in a while and it “sounds” different than you “remember”. Usually it’s not because the amplifier has changed, it’s because your brain has. This is a fundamental concept that is lost on many people.

And this explains why it is so easy for some people to get sucked down the “this amp sounds better than that amp” rabbit hole. Everyone hears the same sound differently. What one person finds pleasant, another may not.

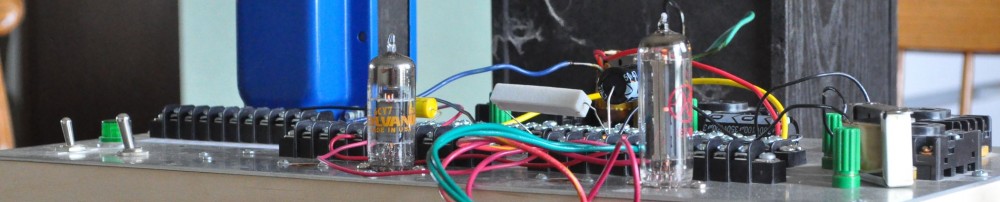

As an example, I personally am not a fan of feedback in audio amplifiers. I simply don’t care for the effects it has on an amplifier’s sound to my ear. But as it turns out, I’ve spent many years listening to simple, zero feedback, SE amplifiers with relatively high levels of 2nd harmonic distortion and very low higher order distortion. And it was precisely this type of amplifier on which I listened to music in my formative years. This has likely reprogrammed my brain to such an extent that I may never really care for feedback amplifiers. But someone that has spent their whole life listening to high open loop gain, high feedback amplifiers, as most commercial audio amplifiers have been designed for the last 40 years, will likely find my amplifiers unkind to their ears. This is NOT to say that my preferred amplifier sounds objectively better than another’s amplifier; or their’s better than mine. Objective assessments are determined with test equipment, impressions are formed with the ear and the brain. And no two are the same.

This is the reason one should never be too quick to pass judgement on the quality of sound out of an amplifier. It’s easy to tell what you like and what you don’t. It’s much, MUCH more difficult to form an objective assessment of the sound of an amplifier. Simply because that is not the way the human brain is wired.

I will agree with you there. I have built several types of conventional solid state amps over the years, and it does seem as if the ones with lower open loop gain, hence less NFB able to be applied, do seem to sound more natural than high open loop gain circuits. The worst offenders are chip amps – almost “infinite” open loop gain, massive NFB, and a very artificial character to their sound, yet very low THD.

Personally, as soon as anything I design and build gets below 1% THD, I’m good to go. That is about the level where virtually no one can hear anything “funny” in the sound.