In the modern western world there is this pervasive, and slightly bizarre, idea that the advance of all things (e.g. technological, medical, political, personal comfort, success, etc.) is a monotonic increasing trend from awful to awesome. And that just because something was once done or existed, then that thing is now “in the books” and there is no reason to ever revisit that thing, whatever it was. It’s a belief that once it’s been done, it’s easy to do again. But the universe is ruled by entropy. And if you stop fighting to reduce it, it just keeps growing.

What got me on this tack this morning was a discussion about space travel but it extends to virtually all technological areas. A recent attempt to place a probe on the moon has experienced problems in route that will prevent the probe from achieving its mission of landing on the moon. Thanks to the wonders of the internet, including comment threads and social media, we can now observe the incredible level of bizarre thought that this single event has spawned.

The most outlandish, at least in my opinion, are the various comments about how this must mean that the moon landings of the last century were faked because 50 years later someone failed while trying to do the same thing. I attribute this idea to the concept I described above. The “we did it before, so now it’s simple” line of thinking. And in reading about this particular story, nowhere did I find even the most insignificant mention that maybe, just maybe, they will learn from this and increase the chances of success next time.

After working on some incredibly advanced technological systems for the last 40 years I have developed a somewhat different view of how things develop (or are lost). That point of view is exemplified by two simple rules. The first of these is this:

#1) There is no shelf

We often hear about things that are “off the shelf”; particularly “off the shelf” technology. This idea is rooted in a belief that once someone (or a group of someones) has developed a new technology and successfully executed it, then it’s now “on the shelf”. As such, anyone that now wants to do the same thing, or something similar, can simply “go to the shelf” dust off the “technology” and do the same thing.

This idea is pervasive and seems to become more engrained the farther people are (intellectually speaking) from actually developing and working with that technology. The idea of space exploration is a good example but let’s look at a different one; cellphones.

Cellphones are ubiquitous. They are part of everyday life for literally billions of people across the globe. There are hundreds of companies that develop and build cell phones worldwide. In theory, it should be relatively simple to go out and develop a new cellphone. So how hard are they to develop? If I start a company tomorrow to build cellphones, what are my chances of success? Starting from nothing, my chances of developing an operational cellphone are pretty small. Almost vanishingly so.

I can increase those chances significantly by hiring lots of people (engineers, designers, technicians, testers, marketers, etc.) who have lots of existing experience designing, building, and selling cellphones. In short, I can hire the knowledge and experience. But can I simply download some designs off the internet? Can I buy a cell phone and copy it? Nope. At least not legally. And even if I could, there are hundreds of examples of companies trying to build products developed by others, and failing miserably. Even when they have all the technical drawings, processes, procedures, test documents, and records. This is because “there is no shelf”. It is virtually impossible to make drawings, procedures, processes, documents, etc. that really capture the most important aspects of any technology. And the more complex the technology, the more true this becomes. The critical parts of any technology are truly stored in the memories, personalities, interactions, and understandings of those who developed them. This applies to everything; from cell phones to space travel.

At its heart this is the reason that “there is no shelf”. Without the people who lived through the process, failed along the way, eventually succeeded, and learned all the lessons, all the documentation in the world is just so much useless paper.

And this brings me to the second rule. It’s this:

#2) There are no experts; only people who have done things lately.

I call this the “Malas Rule” after the person from whom I first heard it many years ago. I have no idea if the thought originated with him or not, but in my mind it is his assertion.

In the modern world it’s almost impossible to avoid seeing, hearing about, listening to, even being lectured by, supposed experts. They seem to be everywhere. On television, on the radio, teaching seminars, in internet videos, being interviewed on news programs, lecturing us at work, at school, or even out in public. These are individuals that someone, somewhere (sometimes simply by the people themselves asserting it) have deemed to be “expert” at something or some topic. But what does it mean to be an “expert”?

Being called an “expert” implies that you’ve arrived at a destination. “I studied hard…”, “I learned a lot about…”, “I developed…”, “I did…”, “I excelled at…”; all past tense. As if you achieved knighthood or some state of nirvana. But what most people really mean by “expert” is that there is such a level of familiarity and skill that one can answer questions, perform technical development and analysis, lecture and explain, etc. with an assuredness and ease which others cannot. There is a lot of shallow pseudo psychology surrounding the definition of “expert” including things like the 10,000 hour rule (i.e. how long doing something does it take to become an “expert”). But not much that really supports it as an achievement.

Most everyone mostly agrees that, in order to become really good at something, you have to do a lot of it; almost constantly. And you have to keep doing it. This is true of any topic or skill; from Engineering to playing an instrument, to complicated mathematics. And if you stop doing it, pretty soon the skill you have begins to fade and get stale. It happens to each person at different rate and to different degrees but it WILL happen to everyone. The status of “expert” is, at best, a fleeting thing.

Hence the rule, “… only people who have done things lately“.

Back to Space

Which brings me back around to space exploration and the mishap with the robotic probe. When people look at the US space program from the 1960s they see large rockets, thundering aloft, carrying space suited individuals on daring adventures. And this is just the vision of history which has been carefully crafted and maintained by NASA and other US government agencies. But it’s really an illusion.

Some History

When one really looks at the history of the work done at Redstone Arsenal and NASA what one finds is not the pretty picture cultivated by history buffs and the US government. It is instead a history of rapid fire developments, failures, injury, and death. It is a history of incredible (and quite possibly insane) perseverance is the face of enormous odds to do something immensely difficult. And it is a history of the people that made it happen.

It’s been said that the biggest failure of the US space program was landing on the moon. Because that achievement was the beginning of the end. The first Apollo mission to get into space was Apollo 7, launched October 11th 1968. This was after a ten year sprint from 1958 encompassing the entire Mercury and Gemini programs involving 14 flights and numerous problems, failures, and injuries. Apollo 1, never even got into the air. On Jan 27, 1967 a launch pad accident killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee. This forced a complete review of all systems and major redesigns of many of them. Five missions and only two and one half years later (averaging a mission every six months) Apollo 11 carried the first men to the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969. This was the major accomplishment. And also the beginning of the end. By December of 1972 and six manned mission later, a very short period of only three and one half years, the last moon mission, Apollo 17, had to fight for the right to even be shown on television. The end had come.

Space flight had become regular, routine, and “off the shelf” as it were. The Apollo program was over. NASA moved on to the much slower paced Skylab and Space Shuttle programs. Skylab lasted less than a decade, falling from the sky on July 11th 1979. For the next 30 years, the Space Shuttle program encompassed most of NASA’s manned spaceflight efforts. Finally being retired in 2011. But the “Space Shuttle” really wasn’t what it’s name implied. The space shuttle never got more that 400 statute miles (≈650km) from the surface of the Earth. A virtual stone’s throw from the surface. GPS satellites orbit at about 20,000 km and geostationary satellites (like the kind used for weather imaging) park at an orbit of 35,786 km. The “Space Shuttle” was really a “Very Low Earth Orbit Shuttle” that lacked any form of in space propulsion except for some very low powered attitude thrusters. The program simply could not provide the experiences and teach the lessons necessary to achieve true space travel. Those were beyond the scope of the job.

Consequences

So what really happened in those nearly 40 years after Apollo and those moon landings was that all the men that were responsible, those that did the actual work, learned the lessons, and had all the experience, retired, aged, and died. And all the experience of that era was lost. Drawings, procedures, reports, and old notes are very poor substitutes for actual experience.

About that probe

So this is where we are today. Today, to where are we supposed to look for the experts on manned spaceflight? To where are we to look for the experts on lunar landing, lunar surface operations? The answer is simple; hard, very hard, but simple. We have to do it again. We have to give the experience and the hard learned lessons to thousands of people that have never done it before. And we have to do it fast enough for them to learn. And we have to keep doing it so they can pass on what they have learned.

Which brings me all the way back around to that omission I noted before. What did they learn today and what will they learn in the weeks ahead? We’ll probably never know. But the one thing I do know is that, if there is ever a hope of keeping the knowledge alive, they have to keep doing it. And when success becomes mundane they have to reach higher. If not, then again, 50 years from now, we’ll be wondering “Why can’t we seem to land a simple probe on the moon”?

For individuals, for organizations, for humanity, the most important thing is to never stop learning, never stop growing, and never stop achieving. If we do stop, then entropy wins. It’s the law of the universe.

As always questions and comments are welcome.

I recently read the book and watched the documentary “Skunk Works”. Almost impossible projects, solved, built and working in very small time scales. I wonder where all that gained knowledge has gone.

I remember an interview with a Russian Cosmonaut discussing one of the first “spacewalks”. His space suit was basic, constructed of rubberised canvas! The pressure in his suit acting in the vacuum of space expanded the suit and his hands came out of his gloves. He couldn’t manipulate his tools or regain entry to the spacecraft. He remained calm, reduced his air supply and vented the suit into space by working a fastening loose. He managed to put his hands back in the gloves. He couldn’t breathe at this point.

He survived because of his amazing presence of mind, but this illustrates the simplicity of the available technology and the danger of his mission.

At the time it was at the limit of Human ingenuity to succeed and perhaps politically it was more acceptable in those times when people died.

Today, efforts seem more fragmented, technology more complex, resources and expertise more widely spread. Maybe more collaborative effort will be needed in the future, since as you say, there is no shelf.

Matt,

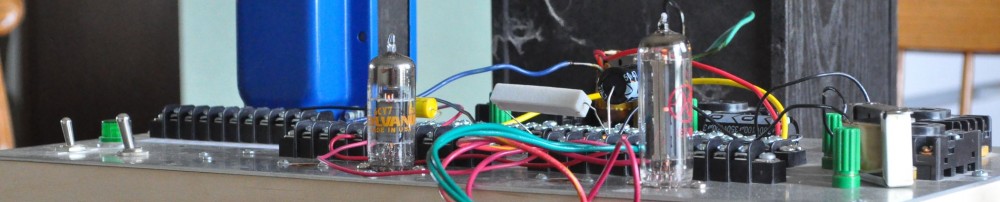

I enjoyed reading your thoughts. They are very fitting for a blog on vacuum tubes – once a prevalent technology that is now more of a niche hobby. The two points are foundational to the projects and studies you create. Thanks for the post!

Dan